Project Protho, Audubon South Carolina’s community science project at the Beidler Forest Audubon Center & Sanctuary, has worked for over a decade studying the Prothonotary Warbler, Protonotaria citrea. This sunny ball of feathers and energy that sings a “sweet-sweet-sweet” song from the heart of shady Four Holes Swamp has kept many secrets about its life during the other part of the year when it’s not at Beidler. We currently don’t know all of the details about what route they take to their wintering grounds, how high they fly, how fast they fly, when and where they stop to refuel, and when they depart either destination. They have lots of little secrets in their little fuzzy yellow heads!

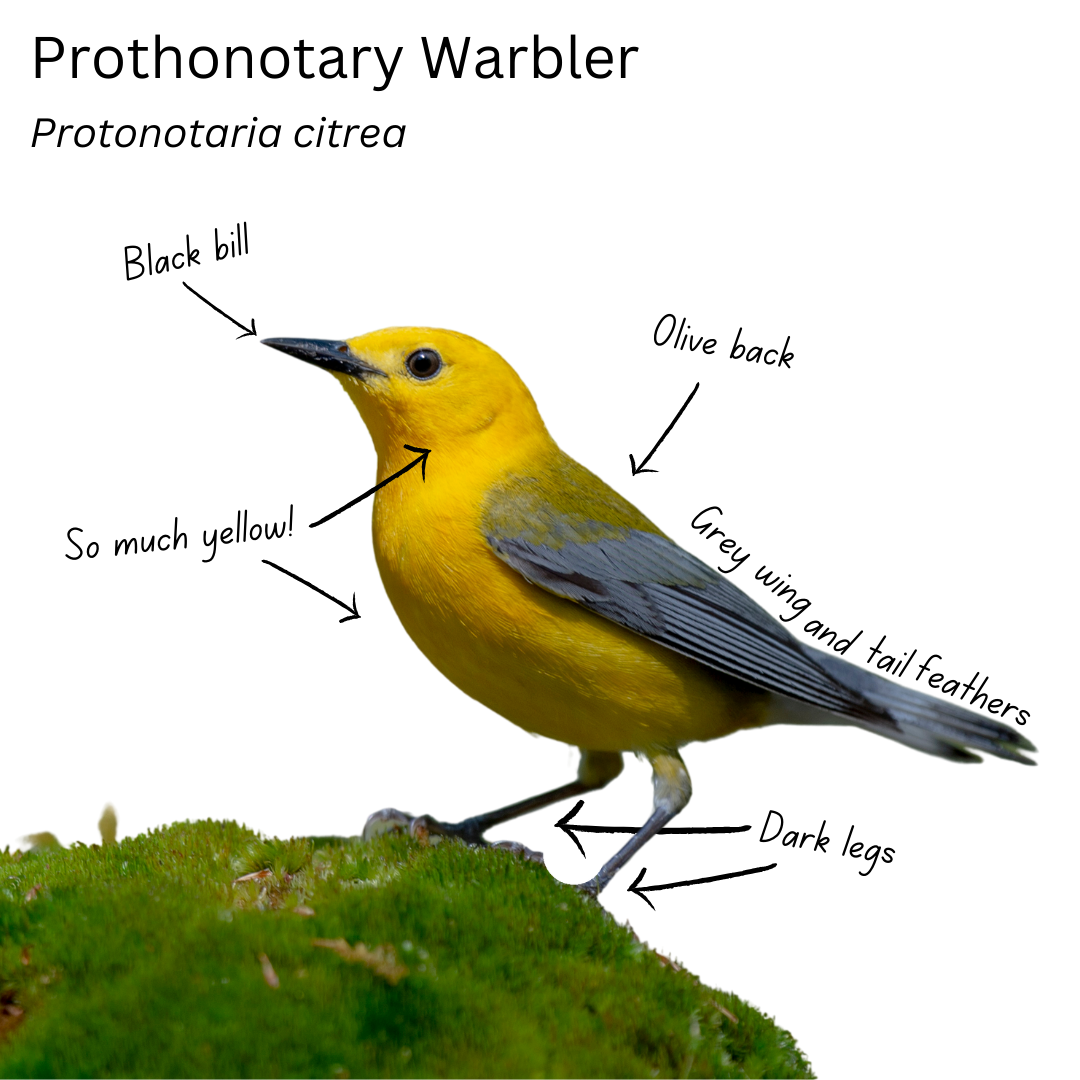

Prothonotary Warblers are a visually striking species of Wood Warbler, and the only member of it’s genus Protonotaria. The name comes from a Prothonotary, which was a papal clerk in the catholic church who wore yellow robes. Another distinctive feature of this species is that it’s the only Eastern wood warbler that nests in cavities. Prothonotary’s use secondary cavities that are naturally occurring or that were previously excavated by a woodpecker. Bottomland hardwood forests are the preferred habitat of this species, but they have suffered population declines from habitat loss when bottomland hardwood is logged or converted to agriculture. They winter in the coastal mangroves and low lying forests of Colombia South America. They feed on mostly on flies, caterpillars, beetles, ants, aquatic insects and snails, and spiders during the breeding season. One of their favorite prey items being the Mayfly, which is abundant in Beidler Forest during the breeding season.

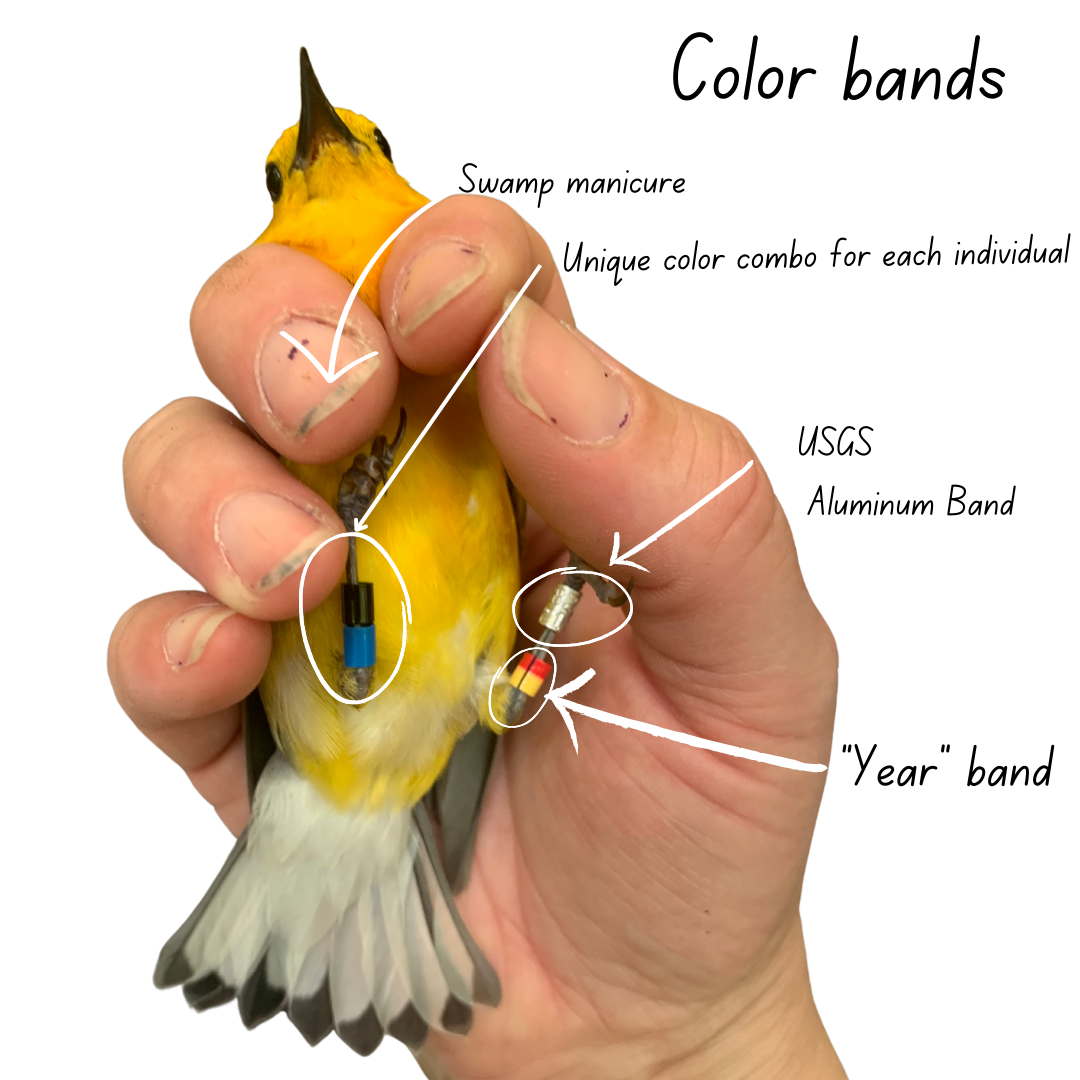

Since Audubon South Carolina has access to some of the highest quality old-growth cypress-tupelo swamp in the world, we have an excellent opportunity to study this species who calls Beidler Forest home. Over the years, many Prothonotary Warblers have been banded for resighting using color bands. These bands allow for anyone to spot the bird from a distance, record the color combination of the bands, and learn which individual bird it is from it's processing history. We've watched many birds return year after year using color bands as identifying markers. Using the color banded birds, we also learned about individual territory sizes along the boardwalk and annual survivability. In 2016, Project Protho, the collaborative project across this species’ range revealed that almost all of the Prothonotary Warblers in North America winter in Colombia, South America. The use of light-level geolocator backpacks to store location data revealed this amazing discovery.

We also work with partners studying the same species across their range simultaneously in a big happy science group project where everyone does their part (unlike the science group projects in high school). This collaboration, called the Prothonotary Warbler Working Group, published the first paper in 2019 revealing that almost all of the Prothonotary Warblers in North America winter in Colombia, South America. This study used a special technology in the form of of light-level geolocator “backpacks” mentioned previously, to store location data.

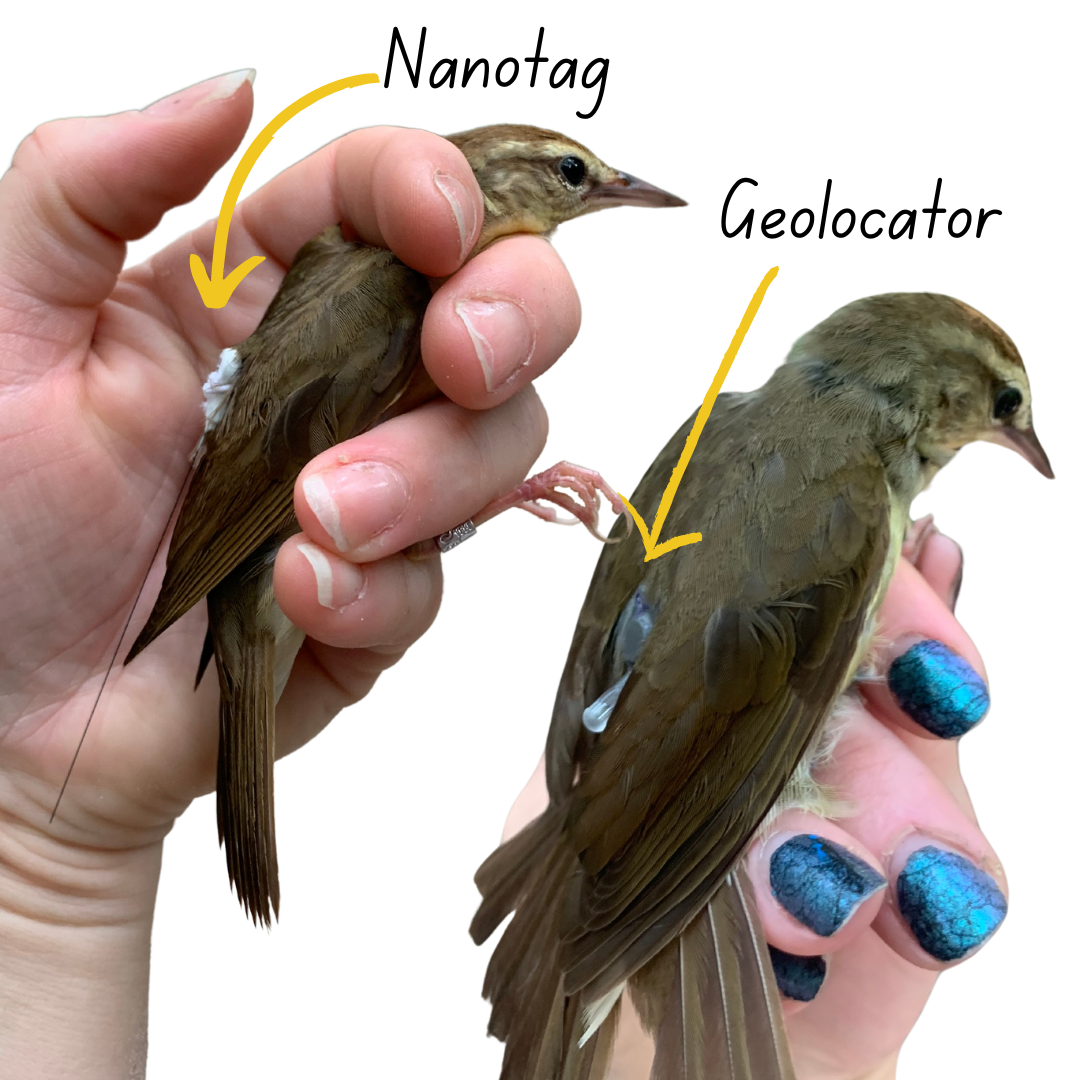

What is a geolocator you ask? Well, it’s a tracking device that lets us know where our warblers spent the winter. This technology has evolved (and miniaturized) over the last decade to be small enough to attach to small songbird like a Prothonotary Warbler. The first round of geolocator deployments at Beidler Forest recorded light levels . These 0.5 gram units collected sunrise and sunset times using a tiny light sensor. The birds of the 2019 geolocator deployment study left our swamps as the tupelo leaves began to turn yellow and fall, and the days grew shorter, triggering Zugunruhe (or nighttime migration restlessness), which in human terms is the anxiety and feeling of “I should not be here, time to go”. The technology these birds carried was fairly basic and was only able to give us the general location of the wintering grounds based on this light level sensor. During the Spring and Fall equinox, the data blacks out and we’re unable to determine a bird’s location with the basic geolocator, leaving a large gap in the migration journey.

Check out Audubon's Bird Migration Explorer to see the tracking data animations of Prothonotary Warblers, and many other species! With the Prothonotary Warbler account you'll see that many of the previosly tracked birds go missing during migration due to the equinox.

After the Winter season, the birds return to the swamp, within feet of where they were captured the year before. Ideally, every bird carrying a backpack returns, but nature is a cruel mistress and migration is a fickle beast, resulting in 40% return rates as a typical best-case scenario. Of the birds that return to the swamp with their backpacks, they need to be recaptured to download the data, meaning they must fall for our ruse once again and fly willingly into our nets. You may wonder how we catch them in the first place? With targeted mist netting, we intend to find and catch one individual bird in their territory that they are very defensive of. So, I roll up in a male’s territory, set up a very fine mesh net that is difficult to see, even for people. I've forgotten where a net was and walked into it before..... on more than one occasion, not my proudest moments. Then, I set in place a bright yellow wooden decoy and a Bluetooth speaker playing a male’s song. This essentially translates to “come at me bro”. An angry male then dives at the decoy to chase that rival "male" out of his territory, and Yahtzee! We have our bird. Well, ideally that's how it all plays out.

Unfortunately for us researchers, birds are smarter than you’d think, and sometimes recapturing individuals is trickier than we’d like. Tagged birds have a saying, fool me once, shame on you human, fool me twice, shame on me, hey look a mayfly, nom nom nom.

Recapturing a bird sounds really difficult, doesn’t it? Now, you may be asking, why don’t we just use satellite tags or some other technology that can send us live information so we don’t have to recapture the birds to download the data? Well, the technology is not small enough yet. Prothonotary Warblers weigh about 15 grams, give or take, which is about the weight of two US Quarters, or six pennies, and you can only attach something to a bird with proper permitting and special permissions that weigh 3% of the bird’s weight so that it doesn’t negatively impact them. So an onboard computer with satellite tracking technology would have to weigh .45 grams, which is the weight of half of a paperclip. That’s a lot of technology in a very small package. Keep in mind it needs to have a battery to operate that will last a year!

“What about Motus tags? Why don’t you use those?”

Motus tags are a great option for many bird tracking studies. Audubon South Carolina has been working with partners across the United States to build out a Motus tower network to detect nanotags. These tags send a signal which is detected by the tower and uploaded to the internet. This method gives researchers close to real-time information without having to recapture the bird to remove the tag and download the data, but there’s a catch. Some species live in dense habitats, like swamps if you will, where their tag signal won’t reach a tower, and some species travel to areas and over open oceans where there aren’t any towers to detect them. So, for the Prothonotary Warbler, the Motus network and Nano-tags aren’t the ideal tool for tracking at this time. Worry not, Audubon and many partners like the American Bird Conservancy, Nemours Wildlife Foundation, and Audubon Americas are working hard to install Motus Wildlife Tracking towers in areas where we think the birds are traveling, but for many neotropical migrants (birds who migrate to Central and South America and back), motus tags aren’t the perfect answer at this time.

Let’s fast-forward. It’s June 2024, the swamp air is as thick as peanut butter, the marauding yellow flies have a relentless thirst for blood, and the Prothonotary Warblers are busy feeding fledglings. Matt Johnson, Beidler Forest Center Director, and I are paddling through four-holes swamp looking for the last few candidates after second year, male, Prothonotary Warblers to outfit with some custom jewelry (color bands) and a backpack. This breeding season we deployed 12 new geolocators on birds at three different sites. Thanks to funding from Duke Energy and Old Santee Canal Park we deployed three tags at Black River Cypress Preserve and four tags at Old Santee Canal Park.

“If you already deployed geolocators and know where Prothonotary’s winter, why are you deploying more?”

Excellent question me! The newest geolocators have more capabilities on board than the older models. The new tags have a barometric pressure sensor which uses a “geo-spatial-temporal” barometric pressure dataset that looks at live pressure readings across the globe. When combined with light level readings, the pressure readings can produce a much more accurate location, and it eliminates the issue of the data blackout during the Spring and Fall Equinox when the sun is directly over the equator.

Some of the newest geolocators also came with accelerometers. With all these tools combined, we will ideally learn what routes Prothonotary Warblers take while migrating. This will help us understand their stop over needs and threats they face during their journey.

We will also get snapshots of their flight times, durations, and altitudes! This will give us an idea of when they are in flight and vulnerable. This could be useful when understanding offshore wind energy impacts on migrating birds and aid in proper citing locations.

Audubon South Carolina was a part of the first study to use these fancy new geolocators on Swainson’s Warblers. The data that came back from those tags was incredibly detailed compared to any other geolocator study before. Having seen the results from this technology firsthand, we were hooked and needed to know more! Learn more about the Swainson’s Warbler research project here.

With the added location accuracy these units provide, we hope to open new doors and strengthen conservation relationships and efforts with partners in Audubon America’s to protect and study our charismatic swamp canaries in their winter homes. One way that we've made major steps in full annual life cycle conservation, is by working with our new "Sister center" Cienaga de Mallorquin in the Colombian city of Barranquilla that has similar habitat that Prothonotary Warblers may use during the Winter. The coastal mangroves of Colombia are a winter habitat type that the majority of this population heavily relies on during the non breeding season. If we want Prothonotary Warblers in our swamps every Spring, we need the coastal mangroves to be protected. With this new information we hope to have a a better understanding about the critical areas these birds are utilizing so that partners can focus conservation efforts where they will be most impactful.

The birds will be leaving the swamp soon, wandering across the upland landscape, combining with mixed foraging flocks to prepare for migration, and then will depart the Lowcountry to head to their winter mangrove homes. Some of these birds will carry the devices with them on their journey that will hopefully reveal detailed new data that will help us and our partners in South America protect and conserve this species throughout its full annual cycle.

Looking for more information on this project, contact us at Beidler@audubon.org.

This work was made possible by Duke Energy, Old Santee Canal Park, and donors! Wish our little yellow friends a safe journey so we can see them next Spring!

How you can help, right now

Boardwalk Tickets

We're open Wednesdays thru Saturdays 9 AM to 5 PM and

Sundays 11 AM to 4 PM.

Beidler Membership

Click here to purchase a membership, which provides free admission for a year and other benefits. We offer both Individual and Family Memberships.

Donate to Beidler Forest

If you wish to support us, please consider donating. 100% of your donation goes back into Beidler Forest.